Remote Auditing: Now and in the Future

April 2021 – Marc Gehrmann – Senior Lead Assessor

A Changing World

Nature has forced us beyond a tipping point, from which we are experiencing significant and unstoppable change. At the end of 2019, only one person on the planet had contracted COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS CoV2. But that changed dramatically in what seemed like the blink of an eye. On the 11th of March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that the outbreak of COVID-19, was officially a global pandemic (1). Just over 12 months later there were more than 120 million cases, and 2.7 million deaths worldwide (2).

“The adoption of

technology to conduct audits from a distance was rapidly adopted in response to the pandemic but it should, indeed must, revolutionise the delivery of audits into the future“.

Governments across the world have implemented stringent social distancing and periodic community lockdown polices, with Australia being no exception (3). Australian policies have seen the closure of state borders, the cancellation of domestic flights, non-essential work restrictions, and tight restrictions for access to hospitals, aged care facilities and disability group homes. All of this has impacted considerably on people, groups, travel, industry and the way business is done across the nation. The auditing sector is no exception.

The disruption caused by the global pandemic has directly impacted certification bodies, certified organisations, and scheme owners alike. While social distancing and isolation are important public health policy, at the same time, monitoring the quality and safety of service delivery in health and human services must continue to assure the safety and wellbeing of society’s most vulnerable people.

Technology Assisted Assessment

Remote auditing, or Technology Assisted Assessment (TAA), is the process of using various technologies to conduct audits from a distance without an auditor needing to be physically onsite. The adoption of technology to conduct audits from a distance was rapidly adopted in response to the pandemic but it should, indeed must, revolutionise the delivery of audits into the future. Thankfully, guidance on the process already exists in the form of the International Accreditation Forum (IAF) Mandatory Document for the use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) for Auditing/Assessment Purposes.

This mandatory document outlines the use of technology during audits (4). This includes utilising technologies to:

- Conduct remote meetings and interviews;

- Review documents and records; and

- Use videotelephony technology for visual access to remote locations (e.g., residential homes, organisation offices).

The use of technology to complete audits at a distance has already been adopted in a range of sectors including, engineering, finance, cleaning of surgical equipment, handwashing compliance, food safety, and for organisational internal auditing (5, 6, 7, 8, 9). A study investigating the future of auditing by surveying the views of CEOs, CFOs, and senior executives from various industries, including healthcare and the public sector, found that two thirds of respondents wanted auditors to embrace technology because they believe that the use of technology has improved the quality of audits (10).

While the literature on the use of remote auditing for health and human services is limited, technology has been successfully used in the delivery of telehealth in areas such as primary health care, general practice, and mental health services, with positive perceptions from both health care professionals and patients (11, 12, 13).

Such research findings provide an evidence base for wider adoption of remote auditing, with significant positive social, economic, and environmental benefits. As stated by Baller, “the future of countries, businesses, and individuals will depend more than ever on whether they embrace digital technologies” (14).

Social benefits

Reducing, or indeed eliminating the need for travel could help to increase diversity of the auditing workforce, making it more accessible to people for whom extensive travel can be a barrier (e.g., people with a disability, people living in rural and remote communities, parents of young children or carers). Reduced travel significantly decreases the physical demands on auditors who often catch very early or late flights and drive long distances before reaching their destination, only to repeat the process again the next day.

In addition, the reduced travel time for auditors during an audit, allows time (which is constrained by cost) to be better used to review high risk areas, and increase sample size. For instance, time limits of on-site audits because of travel may mean auditors sample only a few client incidents records from the total number of incident reports in high-risk areas. This can reduce confidence in the audit process and its outcome. A study by Forbes Insight and KPMG found that 80% of CEOs, CFOs, and senior managers across several industries reported that auditors should use larger sample sizes when analysing critical organisational data and information (10).

Economic Benefits

“The future of countries, businesses, and individuals will depend more than ever on whether they embrace digital technologies” – Baller

The utilisation of remote auditing will reduce the costs for certified organisations where audits require significant travel and overnight accommodation for auditors. This is important for many health and human services in Australia where financial sustainability can be fragile, and for whom mandatory certification is a substantial financial burden (15, 16).

Take as an example, a mid-sized audit requiring five days, two auditors, two interstate return flights, and car hire (based on an actual audit). The total costs of flights, car hire, and travel and meal allowances at the current Australian Tax Office rates is well over $4,000. Add to that the travel, accommodation, and meal allowance costs for organisations where representatives accompany auditors, the total cost savings of a TAA is as much as 20-30%. For remote services, this is even greater.

Environmental Benefits

Our environment has benefited significantly from the global lockdown measures to combat COVID-19. It is estimated that air traffic had halved by mid-March 2020, and in some parts of the world road traffic had reduced by more than 70%, resulting in dozens of countries experiencing falls in carbon emissions of as much as 40% (18).

The adoption of remote auditing will enable continued environmental benefits of reduced carbon emissions. The same mid-sized audit discussed above, required interstate air and road travel to six service delivery sites as well as the organisations head office. The audit required four return flights for the auditors, who were each accompanied by representatives from the organisation – a total of six return flights. Add to this the significant road travel of close to 1000km including travel to and from auditors’ homes, and the road travel of the organisations’ representatives. This example results in a carbon footprint of 1.1 tonnes of CO2 emissions or 20% of the average worldwide footprint of 5 tonnes (19). Extrapolated to the average travel requirements for an assessor per year (approx. 20 return flights, 10,000km car travel) this translates to 9.5 tonnes of CO2 emissions annually. This does not consider the personal carbon footprint of an auditor, with the average footprint for an Australian being 15.4 tonnes, significantly higher than the 2 tonnes worldwide target to combat climate change.

An Evaluation of Remote Auditing

There is limited research within the academic and grey literature in relation to conducting remote audits of health and human services via the use of technology. This short evaluation aimed to provide insight into the use of remote auditing, and focused on two key areas, which included:

- The perspectives of organisations in completing their audits via remote auditing, or TAA.

- Comparing the level of conformity of onsite audits in 2019 to that of TAA in 2020.

The TAA methodology includes the use of technologies:

- Video conferencing platforms including Zoom and Microsoft Teams for interviewing personnel and clients and reviewing sensitive documents and records through screensharing functions (e.g., staff and client files).

- Smart devices such as smart phones and tablets to conduct site inspections to determine the appropriateness and safety of service delivery environments and facilities (e.g., secure medication storage, unobstructed entry and exit points, signage and information displays etc.)

- A secure online portal that allows organisations to securely share key documents with assessors (e.g., policies, procedures, reports etc.).

Client Organisation perspectives on remote audits

To gain insights into the client organisation’s perspective on the use of remote auditing, a short online survey was developed. From 18 May 2020 to 28 August, quality managers or key personnel of organisations who had completed their audit via TAA were invited to complete the online survey. Survey questions were rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Scale options for each question were either level of agreement (e.g., strongly disagree to strongly agree), or level of satisfaction (e.g. very unsatisfied to very satisfied). In total, 98 organisations were invited to take part in the survey, and 33 organisations completed the survey, resulting in a response rate of 34%.

Organisational demographics

A total of 6 standards were audited across the 33 organisations who completed the survey, including:

- Human Services Standards – Victoria (HSS).

- Human Services Quality Standards – Queensland (HSQS).

- National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) Practice Standards.

- ISO 9001.

- National Standards for Mental Health Services (NSMHS).

- Disability Employment Services/ Supported Employment Services (DES/SES).

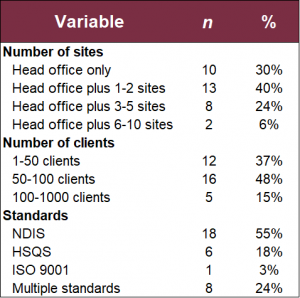

Table 1 shows the key organisational demographics. The largest proportion of respondents completed a TAA against the NDIS Practices Standards, and close to one quarter completed a multi-standard TAA, which included 2-3 standards. Close to half the organisations had between 50-100 clients, and the largest proportion of organisations had a head office and 1-2 sites.

Table 1: Organisational demographics

Results

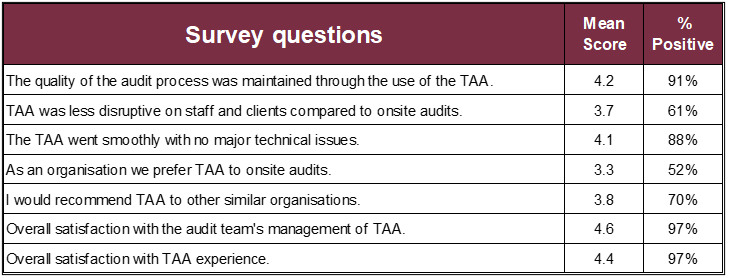

Table 2 shows the mean scores and percent positive (i.e., agree or strongly agree and satisfied and very satisfied) of each survey question.

Table 2: Survey question responses

Overall, 91% (n = 30) of respondents reported that the quality of the audit process was maintained through the use of TAA. Close to two thirds of organisations reported TAA was less disruptive to staff and their clients compared to onsite audits (61%, n = 20), and 88% (n = 29) did not experience any major technical issues during the TAA.

Just over half of all respondents reported they preferred TAA to onsite audits (52%, n = 17), and 70% (n = 23) reported they would recommend TAA to other similar organisations, with only 1 respondent reporting they would not (all other respondents neither agreed nor disagreed).

Overall, 97% of respondents were either Satisfied (30%, n = 10) or Very Satisfied (67%, n = 22) with the audit team’s management of the TAA. Likewise, the majority of respondents (97%, n = 32) reported they were either satisfied (42%, n = 14) or very satisfied (45%, n = 15) with their experience of TAA.

Due to the small sample size, the three organisational demographics were dichotomised into 1-100 clients compared to more than 100 clients; single standard audit compared to multi-standard audit; and 1-3 service sites compared to more than 4 service sites. Chi-square tests indicated no significant differences between the percent positives for each survey question and each dichotomised organisational demographic.

Comparing level of conformity

As a measure of the robustness of remote auditing, levels of conformity were compared between onsite audits conducted in 2019 to that of TAA conducted in 2020. To ensure sufficient sample size, auditors who completed a minimum of five audits across the same standards in each year were selected. This resulted in the selection of eight auditors. Each auditor had at least five years or more experience auditing health and human services organisations and were qualified to audit between 2-4 standards.

Level of conformity was measured by calculating the number of non-conformities in each report and averaging the proportions of each assessor’s total number of reports. A comparison of proportions calculator was used to analyse significance levels.20

Results

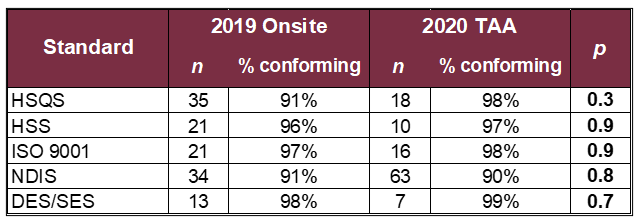

Table 3 shows the number of audits completed by the eight auditors across the five standards in 2019 (n = 124) and 2020 (n = 115). No statistically significant difference was observed between the proportion of conformity from 2019 onsite audits and 2020 TAA.

Table 3: Onsite compared to TAA by standards

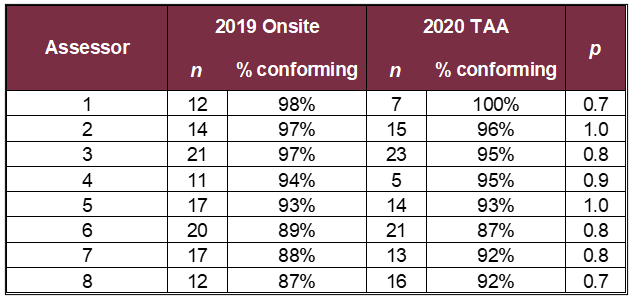

Table 4 compares each auditor’s proportion of conformity from 2019 onsite audits to 2020 TAA. Again, no statistically significant difference was observed.

Table 4: Onsite compared to TAA by auditors

Conclusion

The aim of this brief evaluation was to gain insight into the use of remote auditing, by evaluating how health and human services organisations perceive remote auditing and by comparing levels of conformity between onsite audits and remote audits.

The majority of organisations sampled reported that the quality of their audit was maintained through the use of TAA, close to two thirds reported that TAA was less disruptive for staff and clients when compared to onsite audits, and 70% reported that they would recommend TAA to other similar organisations.

Given willingness to recommend services to others is a key measure of customer satisfaction (21), the findings indicate the majority of organisations sampled in this evaluation viewed TAA as an acceptable methodology for audit.

Using level of conformity as a measure of robustness, this evaluation found that there was no statistically significant difference between onsite audits and TAA, both via the comparison of individual standards and of assessors.

While acknowledging limitations such as a small sample size, the use of a brief online survey, and conformity comparisons limited to the same standards or same assessors rather than two concurrent assessments of the same organisation, the overall findings nevertheless provide positive support for the use of TAA.

Given Australia’s geographical vastness and the financial burden of mandatory audits, the use of TAA could provide significant economic and environmental benefits for health and human services, particularly those in rural and remote areas. Likewise, organisations that have multiple service delivery sites spread across regions and/or states, or a mix of urban, rural and remote locations, could equally benefit from a hybrid model of audit in which the organisation is audited using a combination of onsite activity and offsite TAA.

Future research and evaluation could focus on increasing sample size to support extrapolation across the sector, the use of more in-depth surveys, and identifying other measures to evaluate the integrity of onsite audit compared to TAA.

Overall, the findings suggest that TAA is a viable option for conducting health and human services audits offering substantial social, economic, and environmental benefits while maintaining the integrity of the audit process.

References

- World Health Organization (2020): Virtual press conference on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/

- Johns Hopkins University and Medicine (2020): COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). 26/4/2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- Australian Government (2020): Coronavirus (COVID-19). https://www.australia.gov.au/

- International Accreditation Forum, Inc (2019). IAF Mandatory Document, Issue 2 (IAF MD4:2018).

- Greiner, P. et al., (2019). Remote-audit and VR support in precision and mechanical engineering. Photonics and Education in Measurement Science.

- Siew, E-G., et al. (2020). Organizational and environmental influences in the adoption of computer-assisted audit tools and techniques (CAATTs) by audit firms in Malaysia. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems.

- Pedersen, A., et al (2017). Remote Video Auditing in the Surgical Setting. AORN Journal.

- Lacey, G., et al. (2020). The impact of automatic video auditing with real-time feedback on the quality and quantity of handwashing events in a hospital setting. American Journal of Infection Control.

- Christ, M. H., et al. (2019). Internal Auditors’ Response to Disruptive Innovation. Internal Audit Foundation.

- Forbes Insights (2017). Audit 2025: The Future is Now.

- Johansson, A. M., et al. (2017). Healthcare personnel’s experiences using video consultation in primary healthcare in rural areas. Primary Health Care Research & Development.

- Johansson, A. M., et al. (2017). Patients’ Experiences with Specialist Care via Video Consultation in Primary Healthcare in Rural Areas. International Journal of Telemedicine and Applications.

- Hoffmann, M., et al. (2019). Potential for Integrating Mental Health Specialist Video Consultations in Office-Based Routine Primary Care: Cross-Sectional Qualitative Study Among Family Physicians. Journal of Medical Internet Research.

- Baller, S., et al. (2016). The Global Information Technology Report 2016: Innovating in the Digital Economy. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

- Connelley, F. (2020). The second NDIS shock absorber: The disability workforce. Probono Australia: https://probonoaustralia.com.au/news/2020/02/the-second-ndis-shock-absorber-the-disability-workforce/

- Hough, A. (2018). All care, no responsibility? Government treatment of providers under the National Disability Insurance Scheme and the NDIS Quality and Safeguarding Scheme. Paper presented to the Australian and New Zealand third Sector Research Conference, University of Notre Dame, Australia.

- Australian Taxation Office (2019). Taxation Determination: TD 2017/19. file://hdaa-dc1/FolderRedirections/marc.gehrmann/Downloads/td2017-019c1.pdf

- Watts, J. (2020). Climate crisis: In coronavirus lockdown, nature bounces back-but for how long? The Guardian.

- carbon footprintTM (2020). Carbon Calculator. https://www.carbonfootprint.com/calculator.aspx

- MedCal Software Ltd (2021). https://www.medcalc.org/calc/comparison_of_proportions.php

- Farris, P. W., et al., (2010) Marketing Metrics: The Definitive Guide to Measuring Marketing Performance. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

Looking to get accredited or certified in the health and human services sector? We’d love to discuss your requirements today.